Writing outside the lines

To understand how computers changed the direction of my life, you first have to understand my learning disability: dysgraphia. Dysgraphia is a condition that affects handwriting and fine motor skills and makes writing (and drawing) slow, somewhat painful, and difficult to read. Some estimates have it affecting around 4% of grade schoolers, so it's rare even today. During the mid-1970s, in the small Vermont town where I grew up, it was virtually unheard of.

So it must have been confusing to my second grade teacher to be presented with young Jeremy, who was reading books far beyond his grade level, a regular winner of spelling bees, but who had illegible handwriting. Both hand printing and cursive were difficult to do, but my cursive, in particular, seemed to trigger my teacher. I had developed this “technique” of never lifting my pencil off the paper as I wrote, resulting in entire sentences of connected words. My teacher did not appreciate this.

I was forced to rewrite my work, typically at the cost of missing recess or having to stay after school. This strategy only made things worse, because now my hands were cramped from fatigue and the quality would deteriorate. Seeing no improvement, my teacher would shame me for “not trying hard enough”.

Back home, my mother saw the writing on the wall. (Oh damn, was that just a dysgraphia pun? I think it was.) She saw the writing difficulties affecting my other grades, my self-confidence, and realized the school wasn't going to be of much help. The year was 1977, and the US law guaranteeing accommodations to kids with special needs was only two years old. Public schools were still figuring things out and so something more radical was needed, or a twist of fate. Luckily, both happened.

The Prouty Center

In my hometown of Brattleboro, VT., there was (and still is) a child development institution known as the Prouty Center that was recognized nationally for its ability to diagnose and treat reading problems in children. This institution being located in a town of 12,000 was unusual enough, but the fact it was located one block from my house was downright providential.

My mother managed to make an appointment for me, despite the fact I didn't fit the standard profile. I imagine my situation must have piqued their interest: a child with above average reading ability and below average writing skills. They tested my fine motor reactions and concluded that I indeed had a measurable learning disability. The test results, combined with old-fashioned observation, helped point to the diagnosis of dysgraphia.

Although the diagnosis was useful, challenges lay ahead. Writing is the primary means by which we organize and process information and when you struggle with it, you're simply going to have a BAD TIME learning. In addition, there's another aspect to dysgraphia that's hard to describe: it's a general difficulty in translating your thoughts to paper and it affects everything. Writing, yes, but also drawing. It's as if there's a filter impeding the connection between your brain and hand, making it harder to push your thoughts through, that's the best way I can describe it.

These were the difficulties I had to look forward to in a world where writing by hand was still preeminent. However, all that was about to change.

Thinking in digital

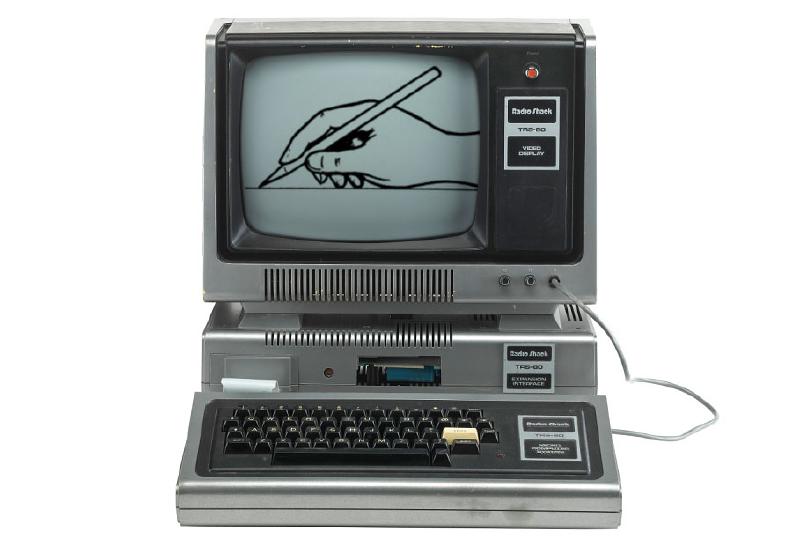

The exact details of what happens next are lost to time, but somehow my mother catches wind of a class involving these new “micro computers” that are beginning to hit the market. Maybe it was an adult education program, maybe it was a local business trying to stir interest in computer sales. Whatever the case may be, it's 1978 or ‘79 and I'm nine years old in a room full of TRS-80 Model I computers and a group of adults. (Chances are slim, but if you happen to have any information on who may have run these computer classes on the second floor of a building on Main Street, Brattleboro, <a href=let me know.)

The TRS‑80 Model I introduced by Radio Shack on August 3, 1977. Seen here with an Expansion Interface and floppy drives.

As it turns out, my brain was made for computers. I could skip the strenuous step of writing on paper and go straight to the screen through the use of the keyboard, which was much easier. I learned how to write programs in BASIC, although programming was not (and still isn't) my calling. Honestly, games were probably what drew my interest at first, but back, then most “games” were really interactive fiction adventures and required lots of typing. Regardless, I was in my element: navigating the file system, memorizing commands, all of these things felt natural to me.

My mom remembers picking me up one afternoon and having to wait as I ran around the room, helping all the noob adults with their assignments. Turns out this was a prophecy of things to come.

Copy and Paste FTW

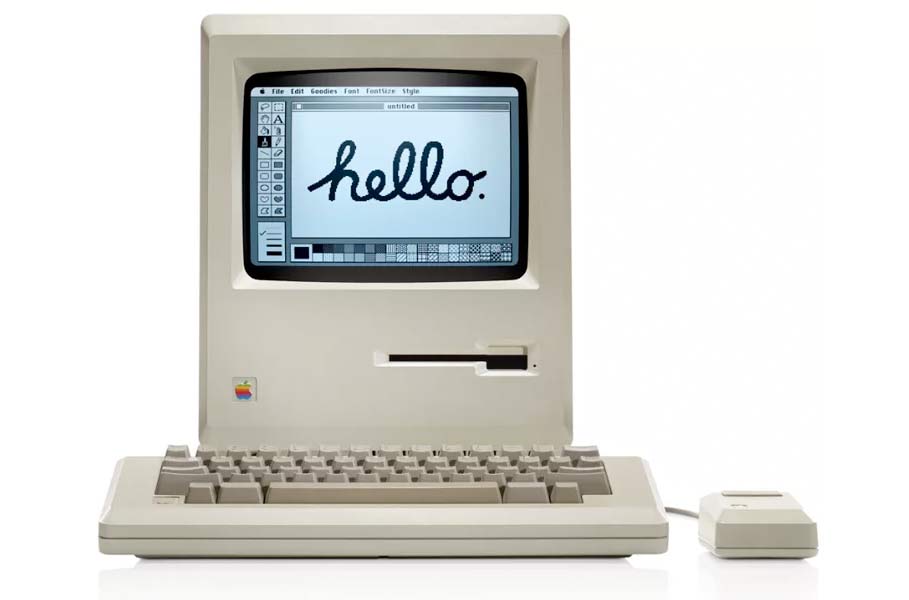

In the subsequent years, computers became a central element in my life. Our school received an Apple II and at home we ended up with a Commodore Vic-20. However, things really changed in 1984 when, through a series of fortunate circumstances, I received a first generation Macintosh computer.

As I write this, that was 35 years ago. I have this system in storage and amazingly it still works! Out of curiosity, I looked up the manufacture date from Myoldmac.net and I found this:

“Your original Macintosh 1984 (128k) was the 8432th Mac manufactured during the 41th week of 1984 in Fremont, California, USA.”

That Mac came off the production line at exactly the right time during my freshman year of high school. At that point, your written work begins to amp up dramatically and the Mac's word processor (MacWrite) became my touchstone. My formative writing experiences throughout high school were all digital, as copy and paste became my friend. Now I could move entire blocks of text at a whim as my disconnected thoughts were captured, rearranged, edited, and finally spit out onto paper with the trusty ImageWriter in nice, orderly rows. All thoughts of being judged by my writing were gone, now all I had to worry about was my ink ribbon running out.

Progress make perfect

As I hinted at earlier, you can draw a shaky line between that 9 year old kid running around the computer class helping adults, to my current career as a design educator. The irony is that even though computers are the medium, when teaching, you still need do a lot of hand-writing. Only this time it's on a vertical surface, in front of an audience of people watching your every move. So, how'd that go for me?

Well, my penmanship has improved through deliberate practice. I still have to go slowly, and there's a conscious narrative running through my head as I form the letters: “Ok, keep the tops aligned, make sure the characters are the same size”. If I have to write quickly though, all bets are off, there is likely a train wreck coming.

It also helps to have a sense of humor about it. In 2005, I was the Program Director for a full-time Graphic & Web Design program at Boston University, this position included a lot of in-class teaching and there were many days where my whiteboard notes were less than stellar. I remember during a post-graduation get together, the topic of writing came up and a graduate said something to the effect of: “Actually, your poor writing was inspiring, because I figured if Jeremy writes like that and could get to where he is in his design career, than so could I!”

How can you not help but laugh?! The truth is, as an educator, I will grab every opportunity to inspire that I can, and if that means putting a disability on full display to the world, than so be it.